'Connexion' - Zemba Luzamba

Collection: 'Connexion' - Zemba Luzamba

06.11.19 – 31.12.19

Cape Town

CONNECTING THE VIEWER TO CONNEXION AND THE WORKS OF ZEMBA LUZAMBA

‘I strongly use the science of forces in my work to empower the subject. Referring to the way I paint, I believe it can hold potential to show, teach, and speak about my mind and the way I see things.’ Zemba Luzamba *

*Kirsty Cockerill, DRESS CODE: THE POLITICS OF DRESS, OPPRESSION AND SELF- DETERMINATION (Cape Town: www.asai.co.za, 2019)

To connect is to bind parts. To bind parts is to build. To build is to advance.

Human nature is hot wired to build, to grow, to advance in whatever direction the human force desires. Within a societal context, the connection of individuals to others starts as family, merges into community and then manifests as a society. Democratic social systems are designed to order this connection, to streamline, to regulate around notions of freedom, fairness and access. Structured to plough the fields for the individual to move forward, and in a global utopian paradise, to concurrently meet the needs of universal human advancement.

Without connection whether it be to an electrical grid or likeminded people, there is stagnation, the warping of unfulfilled potential. In order to advance, a feeling of belonging and access to a market will develop psychological and material comfort. When social systems are flawed, advancement is constrained, human nature however does not change, designed to move forward it twists, contorting ideals to find another way, sometimes brutally, perversely and at its best, with resilience, ingenuity and invention.

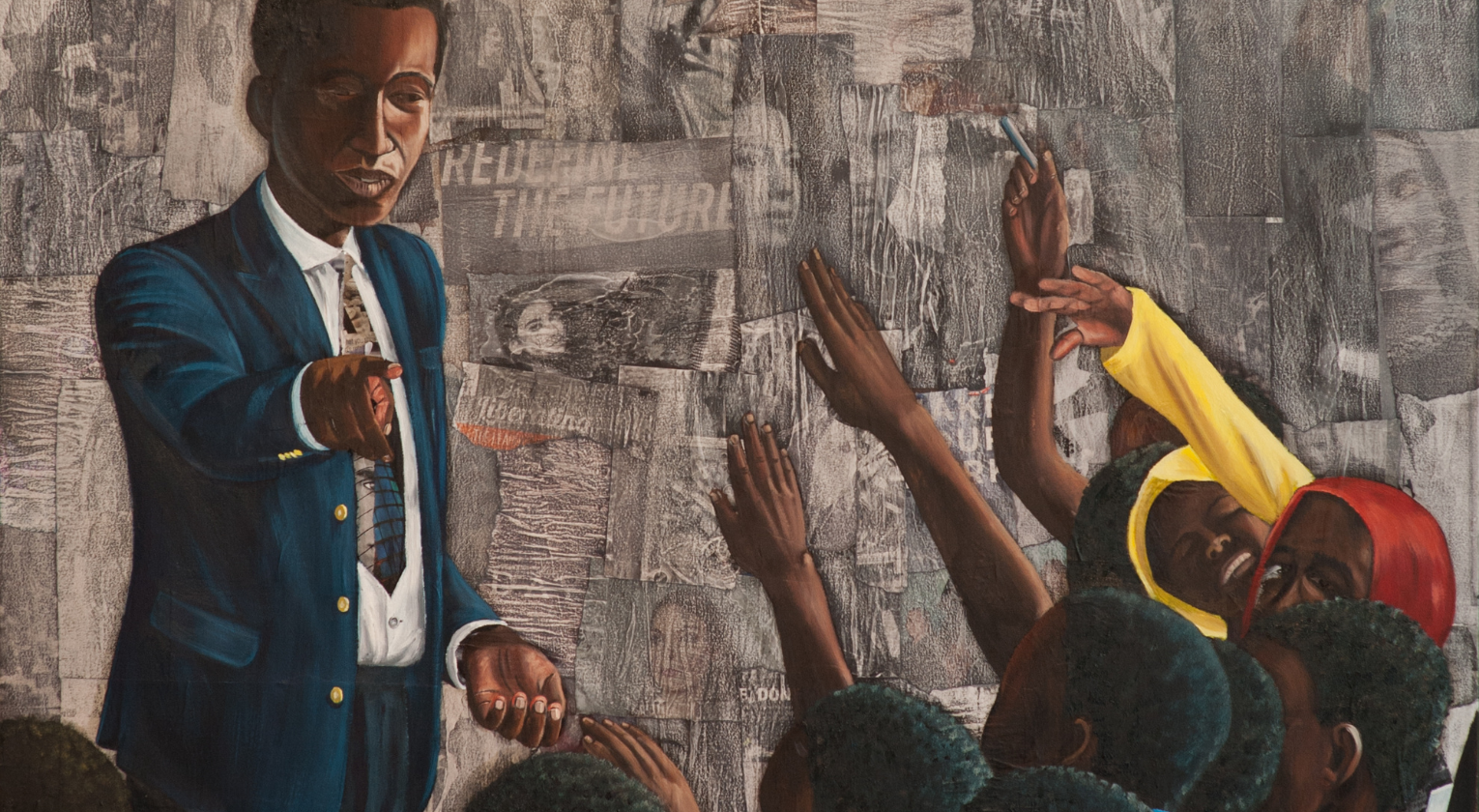

In Connexion, Zemba Luzamba illustrates through visual strategy and narrative symbol, aspects of this fundamentally simple - yet manifestly complex idea.

Using the coding inherent in clothing, style and body posture, Luzamba illustrates power dynamics and societal systems. Sometimes the clothing references are specific to the pageantry of power and politics found in Congolese history, and sometimes they relate to status and class exhibitionism found in global life more generally. In earlier works, the people painted are more often than not mere coat hangers, placeholders onto which symbols of clothing are hung, utilised to represent general archetypes in the dance of power. To a degree the same can be seen in this new body of work, though the shift in the materiality of his visual language opens up ambiguous layers for exploration.

Luzamba’s formal compositions are constructed with two distinct visual planes, the foreground and the background. A middle ground does not feature, there is no soft centre to segway the viewer between the two. This has the psychological effect of making the paintings a reinforcement, a statement, where even historical threads are presented as being of immediate consequence.

In Luzamba’s exhibition La Sape 2013, the artist debuted a way of working where figures were presented in unspecific backgrounds; flat, vibrant colour planes onto which the viewer could imagine or project their own desired context. The paintings presented in Connexion 2019 follow a similar pattern, in so much as the figures offer the dominant clues to reading the content, these paintings do however stand in sharp visual contrast to earlier works. The backgrounds are collaged pictures, flattened stories, narratives reduced to a curtain of text, magazine pages wallpapered onto canvas, a quasi-map illustrating the noisy terrain named Media. Certainly a space of elusive clarity.

Can sense be found in these collaged multiples, these diverse perspectives, these pages of transient necessities? Are back stories important? Luzamba’s new approach remains conceptually generous; which news, which media, which story, which day before yesterday? The backgrounds like media in general, allow for diverse bias in an individual’s exploration of meaning. The viewer bounces between exploring the background and looking to the painted figures for leadership in order to cement reason.

The work titled Wonders 2019 portrays seven women standing as if on a catwalk, sporting identical sleeveless mini dresses with white Peter Pan collars, identical in everything, except colour. Each woman has dressed their hair uniquely, individual style and character assured, in some ways the same, in other ways potently different. As a collective, the different colour dresses read like a rainbow, the pathway to a pot of gold. The cut and style of the dresses first hit the runways and streets in the 1960s, pioneered by British fashion designer Mary Quant.

Zemba Luzamba was born 1973 in Lubumbashi, the same year President Mobutu banned the wearing of blazers, shirts and ties in a bid to purge the Congo of as many signifiers of European colonisation as practical, in his drive to assert his system of control over the country’s populace. The men packed away their suits and stepped into the abacost; the women packed away their fashionable miniskirts, covered their hair with head scarves and wrapped themselves from waist to ankle with African wax-print cloth, ironically made in Holland. Freedom of expression was severely constrained. The transition to what was called ‘The Third Republic’ in 1990, came with the freedom to return to more universal forms of dress. Men could wear a suit and tie without fear of arrest but specifically in relation to the reading of the painting Wonders, one notes that some aspects of Mobutu’s enforced dress code were harder to shake. The notion that reputable women wear long skirts is one. A woman wearing a mini remained frowned upon. The mini skirt is an item of clothing that historically references the independence of women, not just in the DRC but globally. To this day a woman’s capacity to feel safe whilst wearing one in public is closely linked to the way women are treated by the society in question.

The seven women painted onto the papered-over canvas read like individual flames, spectres, part-ethereal part-worldly. The crisp colour and partly solid form are almost assertive, the figures could feel matter of fact if their bodies were not so openly undone, so undressed. An arm, a face, their skin through which background words and images pulsate like otherworldly tattoos. These background offerings stand as markers onto which the viewer aches to attach meaning.

What is the reason for this visual ambiguity, this puzzle of parts where the edges don’t fit, where the background and foreground pull and push in a struggle for dominance? With the bombardment of media in contemporary society, upon which platform do we stand to understand where the painted figures find themselves, how can we find harmony with an internet full of conflicting ideals, what runs through the veins of these women? In the economy of life, which aspects, what information do we bias in our societal value judgements, what must we discard? Broadly speaking, the painted figures in these works by Luzamba stand like trending hashtags, they focus the viewer on a singular aspect within a global struggle for connection.

In the top right-hand side of the painting in question, scrawled in red like writing on a wall the iconic hashtag from South Africa’s recent history ‘Fees Must Fall’ can be seen. The Fees Must Fall movement which took the struggle for the reduction in tertiary education costs all the way to Union Buildings in Pretoria, was lead most notably by women. Quivering through the chin of the woman in the pale coral coloured dress the word ‘Kills’ asserts itself like a bruise, a marker of the brutal landscape women are forced to cushion themselves against. The woman on the far right of the group in the blue dress, sings like a contemporary pop culture reference, seemingly styled like a character from Nigerian musician Tiwa Savage’s music video 49-99, a song that beats to the everyday human hustle for agency and self-improvement.

‘Wonders’ draws together symbolic threads from colonial and post-independence Congolese history, it binds together Nigerian pop culture and the current South African context to illustrate how women struggle, strive and lead in the journey for human advancement. The visual strategy or ‘science of forces’ as Luzamba articulates it, empowers the struggle between the context and the individual, embodying and amplifying the subject matter whilst stimulating the viewer to explore and make connections whilst reading archetypal examples of the concept of connection as negotiated by the artist.

- Kirsty Cockerill, 2019

More exhibitions

-

'TOTEM' - Zemba Luzamba

TOTEM Text by Khanyisile Mawhayi Zemba Luzamba is thinking about animals as...

-

Expo Chicago 2023

13.04.23 - 16.04.23Navy Pier, Chicago USABooth 414 EBONY/CURATED is proud to present...

-

1-54 London 2021 Contemporary African Art Fair

EBONY/CURATED London 14 October – 17 October 2021 We are delighted to...